Introduction

In recent years, large language models (LLMs) have shown remarkable abilities—writing coherent text, coding, analyzing images—yet their resource requirements grow alarmingly. This leads to cost barriers, environmental concerns, and engineering hurdles. We face a reckoning: while scaling up parameters and data yields performance gains, simply throwing more GPUs and memory at these problems becomes unsustainable. Hardware constraints, energy consumption, and deployment demands force us to seek new strategies for optimization.

Indeed, beyond just bigger models, researchers have begun exploring alternatives: compressing model representations (quantization, pruning, knowledge distillation), tailoring architectures (transformers, neural architecture search), and innovating in distributed training. Each of these areas contributes to a broader theme—efficiency. Rather than solely scaling, we must also refine. This first post will establish some essential context, so we can later examine specialized techniques that reduce cost, time, and environmental impact while retaining model quality.

The Scaling Hypothesis

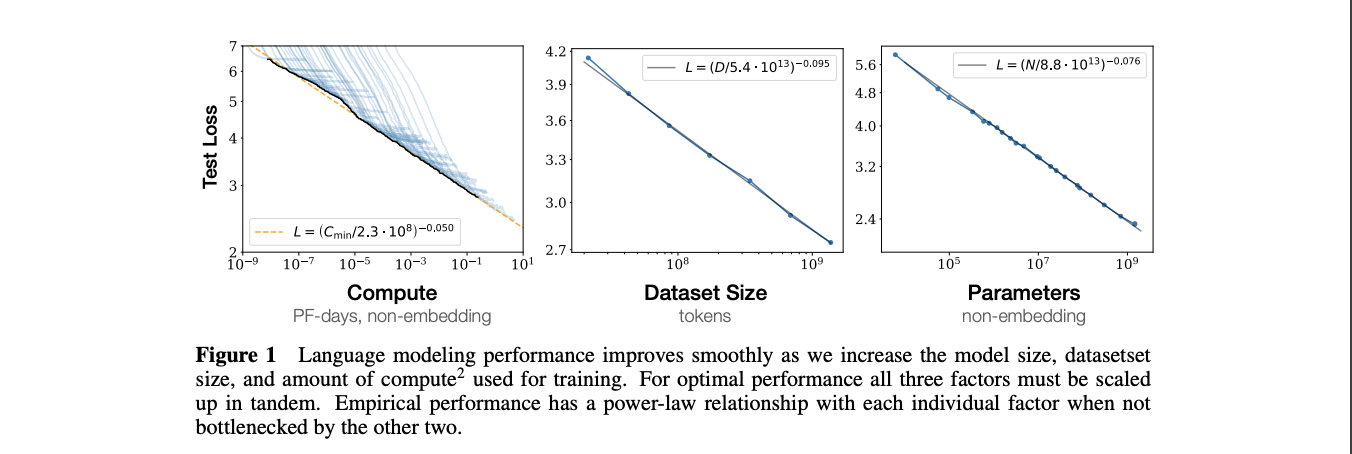

In large language models (LLMs), the scaling hypothesis has proven crucial: train bigger neural networks with more data, and ever more sophisticated behaviors emerge. This parallels the evolutionary scaling from primate to human brains. The earliest detailed statement of this emerged in OpenAI’s “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models” (2020), which noted that test loss follows a power-law in model size, dataset size, and compute. In plain terms, larger models (with more parameters) plus larger datasets plus more compute leads to lower loss—and hence better performance.

This drives the worldwide LLM arms race, catapults NVIDIA’s valuation, and influences how many billions of parameters “Llama” releases (7B, 14B, 70B, 405B, etc.). I will explore the why and how of this in subsequent posts.

Consider a model with (N) parameters trained on a dataset of size (D), requiring compute (C). Scaling them all up in tandem decreases test loss. In practice, we can sometimes predict performance given partial knowledge of (N), (D), or (C). Researchers exploit this to calibrate how large a model to train if you have limited GPU capacity, or to estimate final performance if you push (N) as high as your hardware budget allows.

Hence, if Llama-405B outperforms Llama-70B, it’s precisely because we have more parameters—provided we can feed them enough data.

Model Precision

Parameters can be stored at different floating-point precisions:

- FP32 (32-bit floats)

- FP16 (16-bit floats)

- FP8 (8-bit floats)

Higher-bit precision requires more memory, which matters at large scale. For instance, a 405B-parameter model in FP32 uses about:

That is obviously unwieldy. Real-world deployments typically use more compact representations (e.g., FP16, or even 8-bit quantization).

AI Accelerators

When training neural networks, we do a forward pass (to compute outputs and loss) and a backward pass (to update parameters). These passes are computation-heavy, requiring trillions of floating-point operations. GPT-3’s training, for example, reportedly took on the order of (3.14\times10^{23}) FLOPs, implying tremendous hardware and time demands if done naively.

To train or serve such a model efficiently, three main hardware bottlenecks arise:

- Compute: speed of forward and backward passes

- Memory bandwidth: rate of loading/storing model parameters

- Memory size: capacity of the hardware accelerator

Being first to launch an LLM can secure market share, so reducing training times is vital. Enter the modern AI accelerators, with specialized architectures to handle these tasks swiftly.

Introduction to GPUs

GPUs were originally for rendering graphics. Over the years, they’ve grown into the staple for massive parallelism needed in machine learning, scientific simulations, and cryptography. Key GPU design elements include:

- High Bandwidth Memory (HBM)

- Tensor Cores

High Bandwidth Memory (HBM)

HBM stacks memory vertically on the same package as the GPU, offering thousands of I/O pins. This yields far higher bandwidth—often terabytes per second—than standard GDDR. In deep learning, models constantly shuffle data to/from memory, so memory bandwidth can become the limiting factor. HBM helps ensure large models are not starved of data.

Tensor Cores

Modern GPUs add Tensor Cores, which accelerate matrix multiplications for deep learning. By using mixed-precision arithmetic (e.g., FP16 multiply with FP32 accumulate), Tensor Cores handle large matrix ops in a single operation. This massively boosts throughput on training and inference tasks—provided the memory system is fast enough to keep them busy.

Why Memory Bandwidth Matters

Tensor Cores can do trillions of operations per second. If the memory subsystem can’t feed them data at a comparable rate, the GPU stalls. Hence, effective GPU design balances high compute with equally high memory bandwidth.

The Software Angle

Alongside hardware improvements, software frameworks like PyTorch, TensorFlow, and JAX heavily influence training speed. These frameworks integrate with HPC libraries that manage GPU kernels, scheduling, and data transfer. The choice of distributed training strategies—model parallel, data parallel, or pipeline parallel—further impacts resource utilization. Even the best hardware can underperform if the software stack is not optimized for parallel operations and memory management.

NVIDIA H200 Example

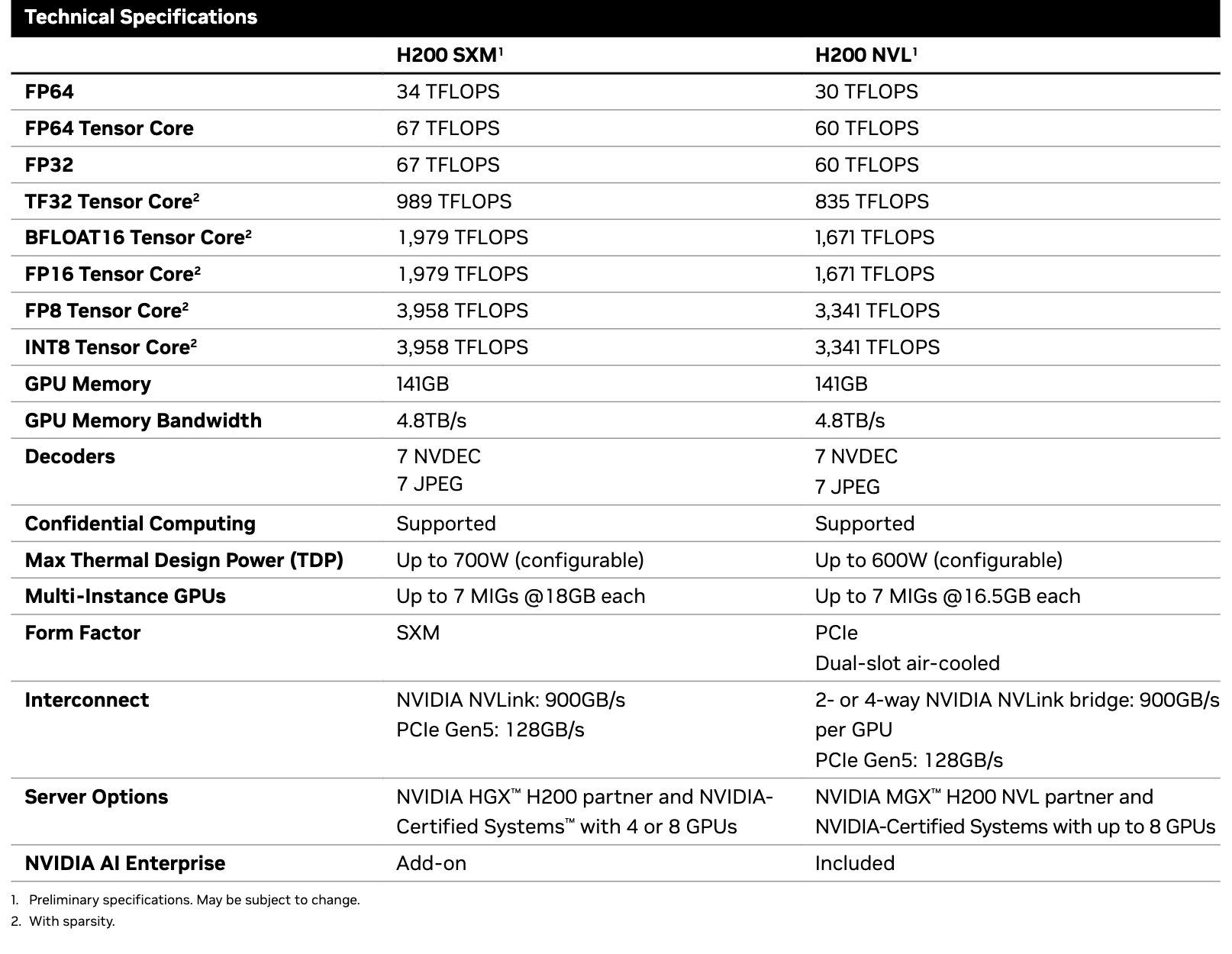

Let’s briefly consider the new NVIDIA H200 (datasheet).

Compute

- FP32 throughput: ~989 TFLOPs. If you tried to train GPT-3 (~3.14e23 FLOPs total) on one H200 at full FP32 speed, you’d need on the order of seconds (~10 years).

- FP8 Tensor Cores: ~3958 TFLOPs. This quadruples raw throughput, reducing that naive 10-year figure to ~2.5 years—still impractical, but illustrative of what lower precision can do.

Memory (Size)

- The H200 has 141GB of memory. GPT-3 in FP32 alone occupies ~700GB, so you’d need multiple GPUs just to hold the entire model in memory.

Memory (Bandwidth)

- The H200’s memory bandwidth is 4.8TB/s. Even if you have enough GPUs in parallel, training speed depends heavily on how fast you can transfer data.

Time to Train, Simplified

If one naive approach divides the model and data across (n) GPUs, each GPU’s training time might look like:

(The factor of 2 is for loading and unloading data chunks.) In practice, you use model parallelism and collective communication to share gradients, so it’s more complicated. But the takeaway is:

- More GPUs more memory and more overall TFLOPs

- Lower precision higher effective FLOPs

- Higher bandwidth less stalling

Thus, training can be shortened, at the cost of hardware expense and engineering complexity.

Distributed HPC Clusters

Beyond a single GPU or even a single node, large-scale AI systems often run on multi-node high-performance computing (HPC) clusters. These clusters orchestrate many GPUs in parallel to reduce total training time. However, scaling to dozens or hundreds of GPUs introduces communication overheads—each GPU must exchange model gradients and parameters, typically using specialized libraries (e.g., NVIDIA NCCL).

As model sizes grow, the percentage of time GPUs spend simply synchronizing data can climb. Efficient collective operations, high-bandwidth interconnects like NVLink, InfiniBand, or 400Gb Ethernet, and custom topologies all help alleviate bottlenecks. Still, practitioners often find that real-world efficiency lags behind raw theoretical FLOPs, underscoring that “adding more GPUs” is no panacea without carefully managing data flow across the entire cluster.

Why We Need Efficiency

Running enormous models is neither cheap nor straightforward. Data centers pull megawatts of power, GPUs cost tens of thousands of dollars each, and the carbon footprints of large-scale training runs grow worrying. Researchers and enterprises want to optimize for minimal cost, faster turnaround, and smaller carbon impact without sacrificing model quality. Efficiency helps ensure that big ideas remain attainable—and not just for a handful of companies with colossal budgets.

We can’t simply turn the “scale knob” forever. Efficient methods—whether they be hardware-based (quantization, specialized memory) or algorithmic (pruning, better architectures, distributed training paradigms)—let us capture the benefits of scale while mitigating the downsides. It’s not just about racing to the largest parameter count; it’s about making the largest count feasible.

Further Environmental and Social Implications

Massive AI training runs demand correspondingly massive energy inputs, straining power grids and increasing global carbon emissions. Some estimates suggest state-of-the-art models can produce emissions on par with entire vehicle lifecycles. These considerations motivate new research not just in hardware efficiency—like better memory systems and specialized circuits—but also in algorithmic techniques that can drastically cut training iterations. Efficiency, therefore, is about more than saving money or time. It aligns AI development with sustainability goals and can open the door for smaller organizations to contribute cutting-edge innovations without incurring prohibitive resource demands.

Conclusion

This post spotlighted the critical pillars of AI efficiency: how bigger LLMs drive performance but impose severe hardware and cost constraints. We surveyed GPUs, memory bandwidth, and the interplay of precision, parameter count, and data size. While brute-force scaling can work, it collides with practical limits—training times stretch to years, hardware budgets skyrocket, and model footprints become colossal.

In subsequent posts, I will outline the broad strategies that aim to balance performance and pragmatism: pruning or sparsifying large models, automating architecture searches for optimal efficiency, quantizing parameters, distilling knowledge into smaller nets, refining transformers to handle longer contexts, and deploying LLMs at scale across distributed clusters. Each technique represents a piece of the puzzle: how do we keep pushing AI forward without exponentially inflating resource use?

By exploring these methods, we can uncover ways to sustain the breakneck pace of AI progress without abandoning reason—or our electric grid—in the process.